On

Friday, 6 January CE 548,

the Jerusalem church celebrated Christmas for the last time on this

date

as the Western church moved to celebrating the birth of Jesus Christ

on December 25,

the

grinch who

stole the story

of christmas

December

13, 2012 December

13, 2012

|

Hark!

The Herald Angels Didn’t Sing

T. M. LUHRMANN

Professor of anthropology at Stanford University

We

are in Advent, but over the transom has come the sobering

news that Image Books has just published a book written by

the pope, “Jesus of Nazareth: The Infancy Narratives,”

in which he observes that there was neither an ox nor a donkey

in the stable where Jesus was born. Nor did a host of angels

sing. They spoke. We

are in Advent, but over the transom has come the sobering

news that Image Books has just published a book written by

the pope, “Jesus of Nazareth: The Infancy Narratives,”

in which he observes that there was neither an ox nor a donkey

in the stable where Jesus was born. Nor did a host of angels

sing. They spoke.

He writes: “In the Gospel there is no reference to animals

at this point. But prayerful reflection, reading Old and New

Testaments in the light of one another, filled this lacuna

at a very early state by pointing to Isaiah 1:3: ‘The

ox knows its owner, and the ass its master’s crib, but

Israel does not know.’ ” A few pages later,

the pope explains that “Christianity has always understood

that the speech of angels is actually song.

He writes: “In the Gospel there is no reference to animals

at this point. But prayerful reflection, reading Old and New

Testaments in the light of one another, filled this lacuna

at a very early state by pointing to Isaiah 1:3: ‘The

ox knows its owner, and the ass its master’s crib, but

Israel does not know.’ ” A few pages later,

the pope explains that “Christianity has always understood

that the speech of angels is actually song.

|

KRAMPUS

He Sees You When You’re Sleeping

and Gives You Nightmares

MUNICH JOURNAL

By MELISSA EDDY

THE NEW YORK TIMES

DEC. 21, 2014

Long before parents relied on the powers of Santa Claus to

monitor their children’s behavior, their counterparts

in Alpine villages called on a shaggy-furred, horned creature

with a fistful of bound twigs to send the message that they

had better watch out.

|

Santa Claus and Satan's Cause |

|

|

|

|

"A

wink of his eye, and a twist of his head,

soon led me to know I had nothing to dread."

Twas'

the Night Before Christmas

Clement C. Moore

The

fact is that Santa and Satan are alter egos,

brothers; they have the same origin.

On the surface, the two figures are polar opposites,

but underneath they share the same parent, and

both retain many of the old symbols associated

with their "father" . . . From these

two paths, he arrived at both the warmth of

our fireplace and in the flames of hell. |

|

|

THE

TRUE STORY

December

25 was the birthday of the sun-god, Mithras,

a  deity

whose religious influence was widespread in the Roman Empire, popular

in the Roman military, during the first centuries of the present

era. Mithras was identified with the Semitic sun-god Shamash, whose

worship spread from Asia to the west where he was worshipped as Deus

Sol Invictus (the invincible Sun) Mithras throughout the Roman Empire.

He drives across the sky in a chariot of gold, the Sun being his eye.

deity

whose religious influence was widespread in the Roman Empire, popular

in the Roman military, during the first centuries of the present

era. Mithras was identified with the Semitic sun-god Shamash, whose

worship spread from Asia to the west where he was worshipped as Deus

Sol Invictus (the invincible Sun) Mithras throughout the Roman Empire.

He drives across the sky in a chariot of gold, the Sun being his eye.

Mithras was born in a cave from Petra, the sacred rock, who later

became Peter, the foundation of the Christian Church. He is believed

to be a Mediator between God and man, between the Sky and the Earth.

It also became the belief of the early Christian world that Mithra

was born of [a] Virgin. He traveled far and wide. He has twelve satellites,

which are taken as the Sun's disciples. The Sun's great festivals

are observed in the Winter Solstice and the Vernal Equinox, i.e. Christmas

and Easter.

There

Goes the Sun

By RICHARD COHEN, OP-ED CONTRIBUTOR

Author

of “Chasing the Sun:

The Epic Story of the Star That Gives Us Life”

December

20, 2010 December

20, 2010

|

WHAT

is the winter solstice, and

why bother to celebrate it, as so many people

around the world will tomorrow? The word “solstice”

derives from the Latin sol (meaning sun) and statum (stand still),

and reflects what we see on the first days of summer and winter when,

at dawn for two or three days, the sun seems to linger for several

minutes in its passage across the sky, before beginning to double

back.

WHAT

is the winter solstice, and

why bother to celebrate it, as so many people

around the world will tomorrow? The word “solstice”

derives from the Latin sol (meaning sun) and statum (stand still),

and reflects what we see on the first days of summer and winter when,

at dawn for two or three days, the sun seems to linger for several

minutes in its passage across the sky, before beginning to double

back.

Indeed, “turnings of the sun”

is an old phrase, used by both Hesiod

(> left)

and Homer (>

right). The novelist Alan Furst

has one of his characters nicely observe, “the

day the sun is said to pause. ... Pleasing, that idea. ... As though

the universe stopped for a moment to reflect, took a day off from

work. One could sense it, time slowing down.”

Indeed, “turnings of the sun”

is an old phrase, used by both Hesiod

(> left)

and Homer (>

right). The novelist Alan Furst

has one of his characters nicely observe, “the

day the sun is said to pause. ... Pleasing, that idea. ... As though

the universe stopped for a moment to reflect, took a day off from

work. One could sense it, time slowing down.”

Virtually

all cultures have their own way of acknowledging this moment.

The Welsh word for solstice [Byrddydd]

translates as “the point of roughness”

[when Rhiannon (left)

gave birth to the sacred son, Pryderi] while the Talmud

calls it “Tekufat Tevet,”

first day of “the stripping time.”

For the Chinese, winter’s

Virtually

all cultures have their own way of acknowledging this moment.

The Welsh word for solstice [Byrddydd]

translates as “the point of roughness”

[when Rhiannon (left)

gave birth to the sacred son, Pryderi] while the Talmud

calls it “Tekufat Tevet,”

first day of “the stripping time.”

For the Chinese, winter’s

beginning

is “dongzhi,” (>

left) when one tradition is making balls

of glutinous rice, which symbolize family gathering. In Korea,

these balls are mingled with a sweet red bean

called pat jook (>

right). According to local lore, each

winter solstice a ghost comes to haunt

beginning

is “dongzhi,” (>

left) when one tradition is making balls

of glutinous rice, which symbolize family gathering. In Korea,

these balls are mingled with a sweet red bean

called pat jook (>

right). According to local lore, each

winter solstice a ghost comes to haunt  villagers.

The red bean in the rice balls repels him.

villagers.

The red bean in the rice balls repels him.

In

parts of Scandinavia, the locals

smear their front doors with butter so that Beiwe,

sun goddess of fertility [and sanity] (left),

can lap it up before she continues on her journey. (One wonders who

does all the mopping up afterward.) Later, young

women don candle-embedded helmets, while families go to bed

having placed their shoes all in a row, to ensure peace over the coming

year.

In

parts of Scandinavia, the locals

smear their front doors with butter so that Beiwe,

sun goddess of fertility [and sanity] (left),

can lap it up before she continues on her journey. (One wonders who

does all the mopping up afterward.) Later, young

women don candle-embedded helmets, while families go to bed

having placed their shoes all in a row, to ensure peace over the coming

year.

Street

processions are another common feature. In Japan,

young men known as “sun devils,”

their faces daubed to represent their imagined solar ancestry,

still go among the farms to ensure the earth’s

fertility (and their own stocking-up with alcohol). In Ireland,

people called wren-boys take to the roads,

wearing masks or straw suits. The practice

used to involve the killing of a wren, and singing

songs while carrying the corpse from house to house.

Street

processions are another common feature. In Japan,

young men known as “sun devils,”

their faces daubed to represent their imagined solar ancestry,

still go among the farms to ensure the earth’s

fertility (and their own stocking-up with alcohol). In Ireland,

people called wren-boys take to the roads,

wearing masks or straw suits. The practice

used to involve the killing of a wren, and singing

songs while carrying the corpse from house to house.

wren

Sacrifice

is a common thread. In areas of northern

Pakistan, men have

cold

water poured over their heads in purification, and are forbidden to

sit on any chair till the evening, when their heads will be sprinkled

with goats’ blood. (Unhappy goats.) Purification

is also the main object for the Zuni

and Hopi tribes of North America, their

attempt to recall the sun from its long winter slumber. It

also marks the beginning of another turning of their

“wheel of the year,”

and kivas (sacred

underground ritual chambers, right)

are opened to mark the season.

cold

water poured over their heads in purification, and are forbidden to

sit on any chair till the evening, when their heads will be sprinkled

with goats’ blood. (Unhappy goats.) Purification

is also the main object for the Zuni

and Hopi tribes of North America, their

attempt to recall the sun from its long winter slumber. It

also marks the beginning of another turning of their

“wheel of the year,”

and kivas (sacred

underground ritual chambers, right)

are opened to mark the season.

Yet, for all these symbolisms, this time remains at

heart an astronomical event, and quite a curious one. In summer, the

sun is brighter and reaches higher into the sky, shortening the shadows

that it casts; in winter it rises and sinks closer to the horizon,

its light diffuses more and its shadows lengthen. As the winter hemisphere

tilts steadily further away from the star, daylight becomes shorter

and the sun arcs ever lower. Societies that were organized around

agriculture intently studied the heavens, ensuring that the solstices

were well charted.

Despite their best efforts, however, their priests and stargazers

came  to

realize that it was exceptionally hard to pinpoint the moment of the

to

realize that it was exceptionally hard to pinpoint the moment of the

sun’s

turning by observation alone — even though they could define

the successive seasons by the advancing and withdrawal of daylight

and darkness.

sun’s

turning by observation alone — even though they could define

the successive seasons by the advancing and withdrawal of daylight

and darkness.

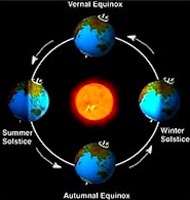

The earth further complicates matters. Our globe tilts on its axis

like a spinning top, going around the sun at an angle to its orbit

of 23 and a half degrees. Yet the planet’s shape changes minutely

and its axis wobbles, thus its orbit fluctuates. If its axis remained

stable and if its orbit were a true circle, then the equinoxes and

solstices would quarter the year into equal sections. As it is, the

time between the spring and fall equinoxes in the Northern Hemisphere

is slightly greater than that between fall and spring, the earth —

being at that time closer to the sun — moving about 6 percent

faster in January than in July.

The

apparently supernatural power manifest in solstices to govern the

seasons has been felt as far back as we know, inducing different reactions

from different cultures — fertility rites, fire festivals, offerings

to the gods. Many of the wintertime customs in Western Europe descend

from the ancient Romans, who believed that their god

of the harvest, Saturn, had ruled

the land during an earlier age of abundance, and so celebrated the

winter solstice with the Saturnalia,

a feast of gift-giving, role-reversals (slaves berating their masters)

and general public holiday from Dec. 17 to 24.

The transition from Roman paganism to Christianity,

with its similar rites, took several

centuries.

With the Emperor Constantine’s

conversion to Christianity in the fourth century,

customs were quickly appropriated and refashioned,

as the sun and God’s son became inextricably entwined. Thus,

although the New Testament gives no indication of Christ’s actual

birthday (early writers preferring a spring date), in

354 Pope Liberius declared it to have

befallen on Dec. 25.

centuries.

With the Emperor Constantine’s

conversion to Christianity in the fourth century,

customs were quickly appropriated and refashioned,

as the sun and God’s son became inextricably entwined. Thus,

although the New Testament gives no indication of Christ’s actual

birthday (early writers preferring a spring date), in

354 Pope Liberius declared it to have

befallen on Dec. 25.

The advantages of Christmas Day being celebrated then were obvious.

As the Christian commentator Syrus wrote:

“It was a custom of the pagans to celebrate

on the same Dec. 25 the birthday of the sun,

at which they kindled lights in token of festivity .... Accordingly,

when the church authorities perceived that the Christians had a leaning

to this festival, they took counsel and resolved that the true

Nativity should be solemnized on that day.”

In Christendom, the Nativity gradually absorbed

all other winter solstice rites, and the co-opting of solar imagery

was part of the same process. Thus the solar

discs that had once been depicted behind the heads of Asian

rulers became the halos of Christian

luminaries.

|

|

|

|

|

Egypt

- Ra |

Buddha |

Buddha |

Roman

- Apollo |

Christian

|

Despite

the new religion’s apparent supremacy, many of the old customs

survived — so much so that church elders worried that the veneration

of Christ was being lost. In the fifth century, St.

Augustine of Hippo and Pope Leo the Great felt compelled to

remind their flocks that Christ, not the sun, was their proper object

of their worship.

While Roman Christianity was the dominant

culture in Western Europe, it was by

no means the only one. By millennium’s end, the Danes

controlled most of England, bringing with them “Yule,”

their name for winter solstice celebrations, probably derived from

an earlier term for “wheel.” For centuries, the most sacred

Norse symbol had been the

wheel of the heavens, represented by a six-

or eight-spoked wheel or by a cross within

a wheel signifying solar rays [the symbol

adopted by Opus Dei, (right)].

The

Norse peoples, many of whom settled in what is now Yorkshire,

would construct huge solar wheels and place

them next to hilltop bonfires, while in

the Middle Ages processions bore wheels upon chariots or boats.

In other parts of Europe, where the Vikings

were feared and hated, a taboo on using spinning

wheels during solstices lasted well into the 20th century.

The spinning-wheel on which Sleeping

Beauty pricks her finger may exemplify this sense of menace.

The

Norse peoples, many of whom settled in what is now Yorkshire,

would construct huge solar wheels and place

them next to hilltop bonfires, while in

the Middle Ages processions bore wheels upon chariots or boats.

In other parts of Europe, where the Vikings

were feared and hated, a taboo on using spinning

wheels during solstices lasted well into the 20th century.

The spinning-wheel on which Sleeping

Beauty pricks her finger may exemplify this sense of menace.

Throughout much of Europe, at least up

until the 16th century,  starvation

was common from January

to April, a period known as “the famine months.”

Most cattle were slaughtered so they would not have to be fed over

the winter, making the solstice almost the only time of year that

fresh meat was readily available. The boar’s

head at Christmas feasts represents the dying

sun of the old year, while the suckling

pig — with the apple of immortality in its mouth —

the new.

starvation

was common from January

to April, a period known as “the famine months.”

Most cattle were slaughtered so they would not have to be fed over

the winter, making the solstice almost the only time of year that

fresh meat was readily available. The boar’s

head at Christmas feasts represents the dying

sun of the old year, while the suckling

pig — with the apple of immortality in its mouth —

the new.

The

turning of the sun was perhaps even more important in the New World

than the Old. The Aztecs, who

believed that the heart harbored elements of

the sun’s power, ensured its continual well-being by

tearing out this vital organ from hunchbacks,

dwarves or prisoners of war, so releasing the “divine

sun fragments” entrapped by the body and its desires.

The

turning of the sun was perhaps even more important in the New World

than the Old. The Aztecs, who

believed that the heart harbored elements of

the sun’s power, ensured its continual well-being by

tearing out this vital organ from hunchbacks,

dwarves or prisoners of war, so releasing the “divine

sun fragments” entrapped by the body and its desires.

The

Incas would celebrate the solar festival of Inti

Raymi by having their priests attempt to tie down the celestial

body. At Machu Pichu, high in the Peruvian

Andes, there is a large stone column called the Intihuatana,

(“hitching post of the sun,”) to which the star

would be symbolically harnessed. It is unclear how the Incas measured

the success of this endeavor, but at least the

sun returned the following day.

The

Incas would celebrate the solar festival of Inti

Raymi by having their priests attempt to tie down the celestial

body. At Machu Pichu, high in the Peruvian

Andes, there is a large stone column called the Intihuatana,

(“hitching post of the sun,”) to which the star

would be symbolically harnessed. It is unclear how the Incas measured

the success of this endeavor, but at least the

sun returned the following day.

Yet above all other rituals, reproducing the

sun’s fire by kindling flame on earth is the commonest solstice

practice, both at midsummer and midwinter. Thomas

Hardy, describing Dorset villagers

around a bonfire in “The Return of the

Native,” offers an explanation for such a worldwide phenomenon:

“To light a fire is the instinctive

and resistant act of men when, at the winter ingress, the curfew is

sounded throughout nature. It indicates a spontaneous, Promethean

rebelliousness against the fiat that this recurrent season shall bring

foul times, cold darkness, misery and death. Black chaos comes, and

the fettered gods of the earth say, ‘Let

there be light.’ ”

So there is good reason to celebrate the winter

solstice — but maybe that celebration is still touched with

a little fear.

|

|

Click

√ on cover to order

|

Celestial

Holidays

EDITORIAL

The New York Times: December 21, 2010

This

is it, the shortest day of the year, the longest night.

Winter, which begins Tuesday at 6:38 p.m. Eastern

time, will get no darker than this. Slowly, inexorably, the

days will begin to yawn wider and wider, and night will begin to contract.

The change is just a few seconds at first — New

Year’s Eve in Manhattan will be only 28 seconds longer than

Christmas Eve. By mid-March, the days will be growing by some

2 minutes and 40 seconds apiece, and then the rate of change slows

again until late June.

We come to the winter solstice with mixed feelings. It will be lovely

to have more light in the day. But there’s something equally

wonderful about these long hibernal nights. By 4:30 every day —

just as the sun is disappearing — we start to feel a little

ursine, ready to dig a hole and sleep away the winter. How different

our species would be if only we’d learned that one great trick!

We are all deeply habituated, in this northern clime, to the annual

accordioning of the day — so much so that an equatorial place

like Quito, Ecuador, where the length of day changes only by a second

from solstice to solstice, sounds almost like a city out of science

fiction. In some ways, that daily constancy seems more disorienting

here, where the length of day changes by almost six hours, than the

reversal of seasons in the Southern Hemisphere, where Christmas comes

in summer.

Another important astronomical holiday follows

soon after the winter solstice (which included a lunar eclipse).

At 2 p.m., New York time, on Jan. 3, the Earth

reaches Perihelion —

the closest approach to the Sun in our elliptical orbit, a little

more than 91 million miles away.

For some reason, this is a moment that

goes uncelebrated, entirely unheralded. So we say to you all,

Merry

Solstice and have a Happy Perihelion!

A FELICITOUS FESTIVUS TO ALL!

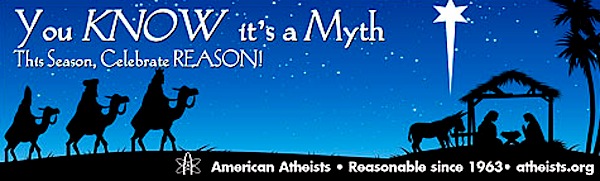

“Attack the myth that Christianity owns

the Solstice season.”

~ DAVID SILVERMAN

President

of American Atheists

EXPOSE

YOURSELF

TO

THE TRUTH!